It took me a while but I finally had the chance to catch up with what has been one of the most talked about movies of the year. “Past Lives” from writer-director Celine Song (in her feature film debut) premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and has since received widespread acclaim. It’s easy to see why. Not only does Song weave together a sophisticated and bittersweet story, she also directs it like someone well beyond their filmmaking years.

“Past Lives” is an endearing drama with a surprising thematic heft to it. Song’s story poses a number of thoughtful questions, among them being the often pondered but rarely answerable “What If”. The film is infused with a heartfelt longing for what might have been while also acknowledging fate and its unpredictable nature.

At the same time Song doesn’t neglect the tender romance at the center of her story – one that mostly goes unspoken. The deep feelings of the two main characters are undeniable, no matter that one person tries to suppress them while the other person won’t quite pursue them. The characters often talk around their feelings yet the two lead performances, especially from the superb Greta Lee, tell us all we need to know.

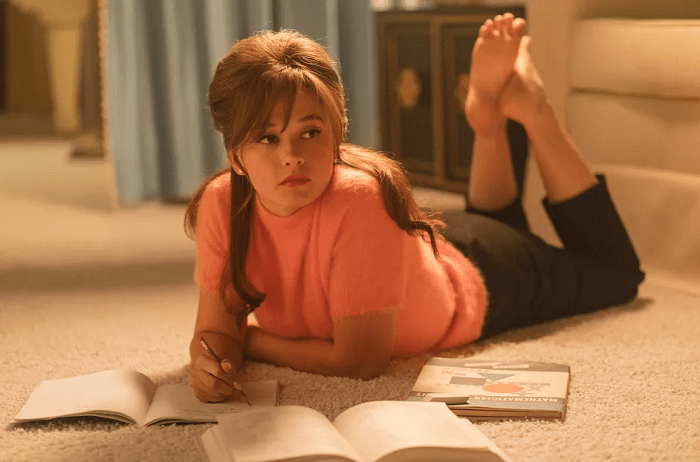

Nora (Lee) and Hae Sung (Teo Yoo) were childhood friends while growing up in Seoul, South Korea. They had a sweet relationship that looked to be blossoming into something more. But then Nora’s artistic parents up and moved their family to Canada. She seems indifferent about the move at the time but Hae Sung takes it hard. That was 24 years earlier.

Twelve years pass and Nora is a writer and playwright living in Manhattan. Hau Sung is still in Seoul where he is enrolled in engineering school. Through the magic of the internet the two reconnect. It’s a bit awkward at first, but the two are quickly reacquainted and soon they are talking to each other everyday via video calls. They want to meet up but neither have the time to make the trip overseas. So Nora decides she wants to take a break in order to focus on her upcoming writers retreat.

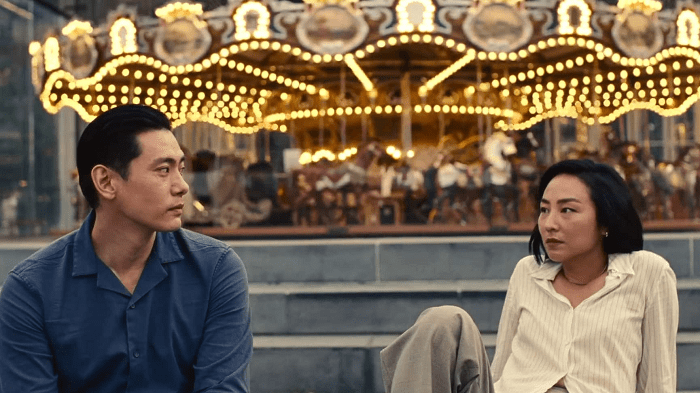

Suffice it to say their “break” turns into another twelve years. During that time Hau Sung did a stint in the military, later met a girl, and eventually broke up with her. Meanwhile Nora met, fell in love with, and married a fellow writer named Arthur (John Magaro). Hau Sung travels to New York for “a vacation” (or so he tells his friends), but he’s really goes to reconnect (again) with Nora. But things have changed dramatically since they last spoke. Have they missed their window? Did they ever really have a window?

Of course the two reunite and I won’t dare spoil how it goes. To her great credit, Song shows remarkable maturity and control by never letting her movie veer into cliche. She maintains a steady authenticity in how she defines her characters and their complicated relationship. The charming chemistry between Lee and Yoo is essential. Lee is the standout, always working at just the right temperature in what is an emotionally complex role. It’s one of my favorite performances of the year.

Equally impressive is Song’s smart and assured work with the camera. Aided by her DP Shabier Kirchner, she fills her film with evocative city imagery, first in Seoul and later New York City. It’s shot in beautiful 35mm film with no extravagant flourishes to speak of (a couple of great tracking shots excluded). It’s hard not to be enamored with the meticulous compositions she spreads across three distinct periods of time. It’s yet another testament to Celine Song’s strong instincts as a filmmaker, and her debut feature marks the emergence of an exciting new cinematic voice. I can’t wait to see what she does next.

VERDICT – 4.5 STARS