Writer-director James Vanderbilt’s riveting “Nuremberg” chronicles key events surrounding one of the biggest trials in world history. The Nuremberg Trials were a joint Allied effort to prosecute captured Nazi leaders following the death of Adolf Hitler and the fall of the Third Reich. The purpose of the trial was not only to convict the Nazi High Command, but to also present irrefutable evidence of Nazi atrocities to the world while discouraging the defeated Germans from following the same path they did after World War I.

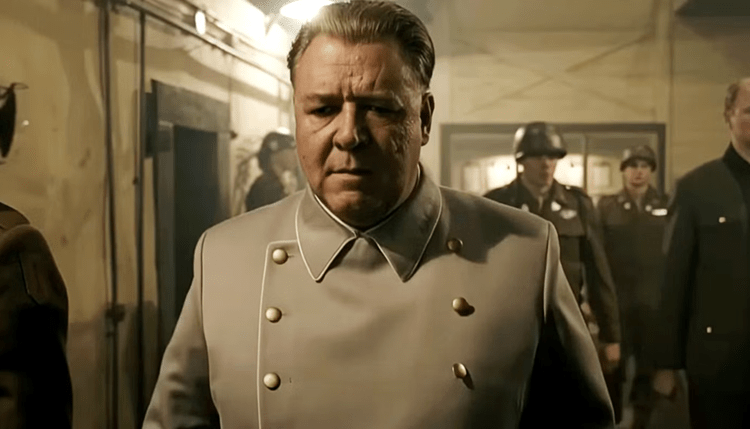

The highest ranking Nazi put on trial at Nuremberg was the Führer’s second in command, Hermann Göring. Highly intelligent, fiercely loyal, and grossly narcissistic, Göring expanded his role as the Supreme Commander of the German Air Force to become one of Hitler’s most trusted officers. His arrogance and cunning were on display at Nuremberg, with both working for him and then later against him.

Inspired by the 2013 nonfiction book “The Nazi and the Psychiatrist” by Jack El-Hai, Vanderbilt’s “Nuremberg” focuses more on the buildup to the first trial than the a trial itself. It’s an effective approach that gives us clearer insight into how the prosecution’s case was built. It also allows us into the head of Hermann Göring, as seen through the commanding performance of Russell Crowe, who deserves nothing less than an Oscar nomination for his astonishing portrayal.

Set mostly in 1945 and 1946, “Nuremberg” begins in Austria with Hermann Göring surrendering to American troops. He’s taken to the Grand Hotel Mondorf in Luxembourg which has been turned into a secret prison to house Nazi war criminals. Meanwhile the Allies are struggling to find the best way to hold their prisoners accountable for their crimes. After much deliberation and internal wrangling, they decide on an international tribunal to take place at the reconstructed Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany.

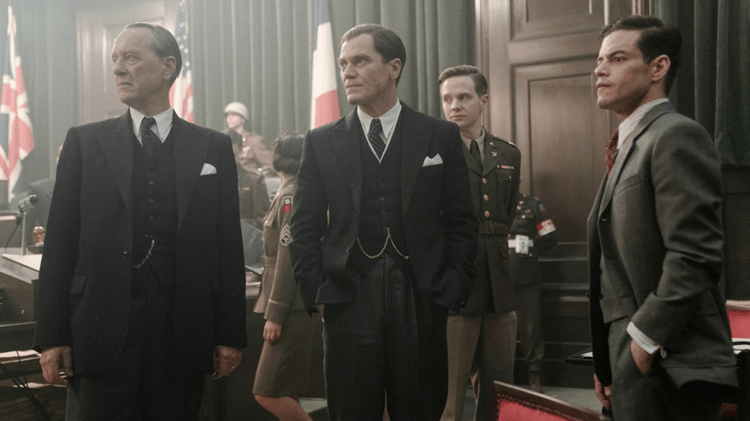

The steadfast yet slightly insecure Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson (Michael Shannon) is sent to Nuremberg to represent the United States on the prosecution team. He’s joined by the savvy and straightforward British prosecutor David Maxwell Fyfe (Richard E. Grant). As they are working through logistics problems, lack of precedent, and untested case law, U.S. Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek) is summoned for a specifically challenging task. He is to evaluate Göring and his fellow Nazi prisoners until they face justice in front of the entire world.

Much of the movie is centered on the numerous meetings between Kelley and Göring. Kelley’s plan is to earn Göring’s trust and to exploit his overconfidence. By doing so, not only would he be gaining insight for his superiors, but he could also collect data for a honey of a book deal once the trials are done. But what he doesn’t expect is for the calculating Göring to be playing his own game, turning on the charm and using Kelley’s empathy to his advantage. It’s a mesmerizing psychological chess match energized by two stellar performances. Crowe is especially good, luring us in just as he does Kelley.

A strong and sturdy supporting cast reinforces the already powerful script. In addition to Shannon and Grant, Leo Woodall gets the film’s most memorable monologue playing Sgt. Howie Triest (Leo Woodall), a young American translator with a sobering connection to Germany. John Slattery is appropriately leathery as Colonel Burton C. Andrus, the commandant of the Nuremberg Prison. And Lotte Verbeek pulls some unexpected humanity from Göring’s wife Emmy.

The trial itself plays out in a stunning recreation of the palace courtroom. By putting the time and effort into building up to the moment, the trial sequence packs a surprising emotional punch. The anticipation in the opening shots, the discomfort that fills the room once Göring and his fellow Nazis are ushered in, the tension in every question and answer – it all keeps you glued to the screen. But the most sobering moments come with the inclusion of the film footage from inside the concentration camps. It’s the same footage shown during the real trial and it will leave you speechless.

“Nuremberg” ends with a powerful quote from R.G. Collingwood, “The only clue to what man can do is what man has done.” Those words echo well after the film’s final credits have ran. Yet even before that, Vanderbilt keeps that central thought in the forefront of our minds throughout his enthralling drama. Not only does “Nuremberg” offer a powerful historical account, but it has an incisive current-day relevance that makes it even more potent. Perhaps it could have gone deeper. But it’s perspective is crystal clear, and its conveyed with sincerity and urgency.

VERDICT – 4.5 STARS